|

1894-1968 |

|

|

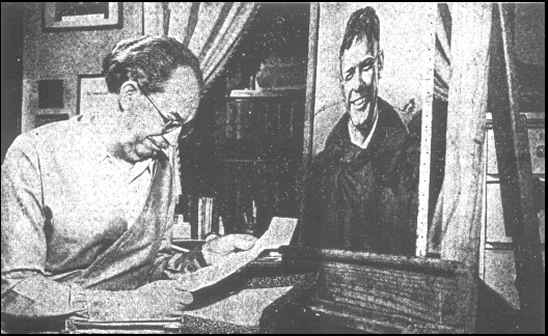

as the portrait nears completion Aviation Leaders "Done in Oils" By Portrait Painter by MARGARET TAYLOR DAILY NEWS STAFF WRITER News Photos by Bill Simmons Dayton Daily News, January 25, 1948 Courtesy of Clark R. Cowley |

|

"Gee, those pictures look like they're ready to talk," exclaimed the newspaperboy. His bike had broken down on Emerson Ave., and he had asked permission to use the telephone at the house numbered 1854. The front room contained not only a telephone but an art studio as well. Portraits done in oil paint hung all around. On the bare floor, leaning against the wall, were stacks of paintings, six, eight and 10 deep. A gigantic easel on wheels towered in the middle of the room. Tubes of pigments, jars of upended brushes, and palettes gobbed with paint gave the room a thoroughly Bohemian appearance. The long-haired, greying man who had opened the door for the newspaperboy was Lewis Eugene Thompson. A few weeks later, opportunity knocked at the same door, and again the artist was courteous and hospitable. As a result, 30 painting bearing his signature are on exhibit at the Institute of Aeronautical Sciences in New York city this week (Jan 25 through Feb. 1). A NATIVE of Michigan and a graduate of Hillsdale College, Thompson come to Dayton in 1942 to get a job at Wright Field. He spent the war years painting portraits of newly-designed airplanes, front views, side views and top views. His attractive oil paintings played a supporting role in the drama of deciding which planes were worthy of development. After the war, Thompson established a private practice, painting by commission and giving art lessons. Although he has always preferred portrait painting to other types of work, he has had a great deal of experience in various fields of commercial art to earn his bread and butter. Portrait painting supplies the jam. While he was working at the Field, Thompson had an idea. He had become very much interested in aviation and decided to start a series of portraits of persons influential in the development of American aviation. He has completed 61 portraits for the series. Thirty of these are now on exhibit in New York. And he has collected the materials for at least 100 more. Getting the material is half the battle. First Thompson must read all available biographical data about the individual to determine whether or not he (or she) is (or was) important enough to the field of aviation to be included in the series. If the individual's contribution to aviation warrants inclusion and if the person is living, Thompson starts a correspondence to check biographical data. His files are bulging with statistics on who's who in aviation. Dayton, the home of aviation, has been the souce of much information. If the subject for a painting has been awarded medals, Thompson may have to request photographs of the medals in order to reproduce them accurately. He goes to a tremendous amount of work to be sure all details are correct. "I EXPECT to be panned by the critics for these portraits," Thompson says, "because I have violated one of the cardinal principles of portrait painting. I have painted in the background objects which represent the contribution of the particular person to American aviation." His portraits remind the observer of Time magazine covers. |

|

|

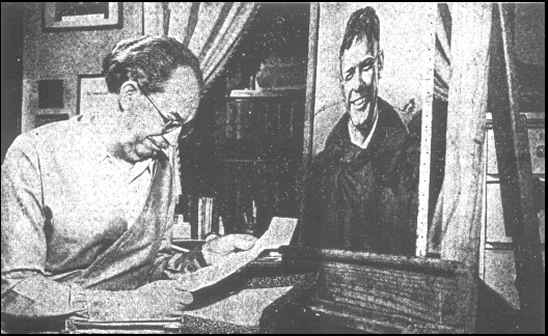

Amelia Earhart, Eddie Rickenbacker, Orville Wright in back |

|

For example, in the background of Orville Wright's portrait is a bust of Wilbur Wright; and at one side of

the painting, resting on a desk, is a model of the airplane in which the Wright brothers made their first flight. Behind Eddie Rickenbacker

hangs an Eastern Air Lines insignia, (he is president and general manager of the airline), and the insignia of the 94th Aero squadron, his

World War I group. In Charles E. Taylor's picture is a model of the first engine ever used for flying, which he designed and built, and a

reproduction of a photograph of the 1908 flight at Fort Myers, Va., at which the government decided to buy the Wright brother's plane. Even if he does the painting from a photograph, he likes to have a personal interview with the subject. He has traveled many miles for these interviews and has had many notables in his studio for an evening. He talks to the subject, watches expressions and jots notes on coloring. "A photograph is static, " he says, "but from talking to the person I can get an idea of what he is really like." After finishing a portrait, Thompson photographs it and sends the photo to the subject. Most of the subjects are well pleased, but a few have complained that Thompson made them better looking that they really are. "Add a few more wrinkles, and make the scar show more," was Mrs. George C. Kenney's suggestion regarding her husband's portrait. In painting portraits, Thompson first plans the composition, then sketches the face on canvas with charcoal. When he is satisfied with his sketch, he outlines it in oil paint because the charcoal would rub off. He applies base coats of paint to the canvas and begins to paint the portrait, light colors first, gradually shading the lights into darks where necessary. He likes to keep nine or 10 pictures going at a time; it provides variety and allows him to work on one while the others dry. |

|

|

at Institute of Aeronautical Sciences, New York, this week. |

|

THOMPSON's portrait of James H. Doolittle will be unveiled at a dinner honoring Doolittle; who was

elected an honorary fellow of the Institute of Aeronautical Sciences, one of the highest honors the aircraft industry can bestow. The

dinner is to be part of the 16th annual meeting of the Institute Jan. 26 to 29. Doolittle has seen a photograph of his portrait and thinks it is a fine likeness. Even so, the quality of Thompson's work remains to be judged by the critics. Thompson is confident the aviation portraits are good enough eventually to be purchased by the government for exhibit in a museum, possibly at Wright Field. The exhibit in New York this week may be the first step toward national fame. Certainly, to the untrained eye his portraits appear to be excellent. They look as if they really were about to speak. |

|

|

|

Contributed by DavidBuerk, 1-2-11 |

|