| Document created: 17 August 05 Air & Space Power Journal - Spanish Third Trimester 2005 |

|

Between the Myth and the Reality by Mario E. Overall |

|

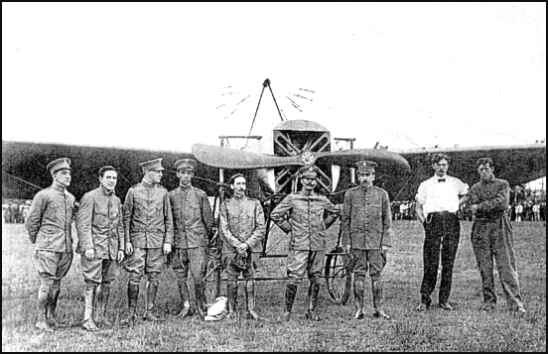

| Members of the Military school. From left to right, in front of the Bleriot XI airplane:Jorge de la Riva (Student), Dante Nannini (Instructor), Unidentified, Unidentified, Luis E. Ferro (Director), General Luis Ovalle (Minister of War), Unidentified, N.E. Bang, (Mechanic -- Moisant Aviation School), Murvin C. Wood, (Instructor -- Moisant Aviation School). Photo taken on the day of the foundation of the academy (June 30, 1914.) |

|

The official version of the beginnings of aviation in Guatemala mentions - invariably - that the precursor was a Guatemalan of Italian

origin, Dante Nannini. In fact, historians and others interested in the subject accept this version verbatim and without question. Poorly

documented articles published throughout the last century, more inclined to the lyrical rather than to the truth, render honors to Nannini

and even minimize the participation of other persons and foreign institutions who played roles of supreme importance in the

development of aviation in Guatemala, this for the sake of emphasizing a nationalism poorly handled that finally finished distorting the

reality of the facts. In any case, and in spite of being inconvenient, the true precursor of aviation in Guatemala was the Mexican Luís E. Ferro, an obscure individual who arrived in the country in 1910 with the intention of establishing a private flight school. Nevertheless, Ferro did not bring a single penny to the stock-market and to make matters worse, he did not even have an airplane with which to start the school. Shortly after arriving in the Guatemala City, Ferro put several announcements in local newspapers, offering his services as aviator and flying instructor, thus hoping to attract a few interested parties who would finance the purchase of the essential airplane. Nevertheless, because of not having an aeroplane and because of requesting down payments, he quickly found himself in a difficult situation and the project had to be abandoned. That failure earned him the nickname of Aviador de Tierra, (Ground Aviator), by the Guatemalans who knew him, and by those who he soon learned to hate. Far from being discouraged, Ferro wasted no time and he made contact with the Moisant Aviation school, located in Long Island, New York, and asked for aid, since according to him, he had managed to make a contract with the Guatemalan Government to establish a Military school of Aviation. Actually, this proposal was not valid. While Ferro waited for an answer from the Moisant School, he finally managed to put himself in contact with the Guatemalan President, Licenciado Manuel Estrada Cabrera, and tried to convince him to establish an Academy of Military aviation, hoping to interest him in the possibilities of using airplanes as military tools and in addition using aviation as an excellent form of public relations by means of shows. Coincidently, in April of 1912, Swiss aviator Francois Durafor, test pilot of the Deperdussin aircraft factory, arrived in Guatemala City, offering several models of military airplanes to the Government. With that intention, Durafor made eight demonstration flights in a Deperdussin Racer on the Campo de Marte field, to the south of the city, generating substantial interest and enthusiasm in the population, although not in the president, who, after being present at several of the flights, declined the offer of Durafor, and also rejected Ferro's proposals with respect to the establishment of a military aviation school. After several weeks, Ferro returned with his proposal: This time, telling the president that the Salvadoran military had already constructed an airplane locally, a statement not actually true inasmuch as the Salvadorans were far from finishing the apparatus, finally convinced Estrada to create the Military school of Aviation, and to acquire an airplane to equip it. The Guatemalan President simply could not allow such an desequilibrio armamentista, (imbalance in armament), in the region with respect to his El Salvador neighbor. Ferro was designated as Director of the incipient Academy of Aviation and was authorized to purchase the equipment. Shortly thereafter, the long awaited response from the Moisant School arrived in the form of a letter; in which the School offered to send a pilot/instructor and a mechanic, but with the proviso that an airplane had to be purchased by the government. In satisfaction of that requirement, the sale of two apparatuses was made, a Bleriot XI and Nieuport-Moisant 6M at a cost of $750 each. Ferro wasted no time and accepted the offer. Finally, in May of 1914, the airplanes, the pilot and the mechanic arrived in the country, although the official ceremony that would mark the foundation of the academy was not set until the 30th of June. It was at this point and not earlier that Dante Nannini arrived in the country from the United States, and was assigned as flying instructor in the Academy of Aviation, obviously under the command of Ferro. In any case, the foundation of the Academy marked the beginnings of the involvement of the Moisant School in the development of Military aviation in Guatemala. The true Guatemalan pioneers would learn to fly with instructors provided by that school, the most prominent of them being Murvin Wood, who later would break the speed record flying between New York and Washington. Another of them no less important, who also was in Guatemala, was the Lebanese Shakir S. Jerwan, who acted as Head of Instructors of the Moisant School for many years. Both persons are remembered as being true pioneers of the air of the United States, belonging to the select group, Early Birds of Aviation. The presence of the Moisant School instructors in Guatemala continued for four long years, only ending in 1918, shortly after the outbreak of World War I when they were replaced by a aeromilitary mission sent by the government of France as part of an assistance program. As might have been expected, when the French came into control of the Military school of Aviation, Ferro was dismissed immediately, this in spite of the friendship that the Mexican had cultivated with the old Guatemalan president. Shortly thereafter, it would be discovered that Ferro was in fact not an aviator and had remained in the position solely by virtue of his dubious talent and the protection of the president. In fact, when a territorial conflict with Honduras exploded at the end of that year, Ferro was a member of the negotiating commission, acting as the eyes and ears of the president from within the group. With respect to the airplanes that the Moisant School had sold to the Guatemalan Government, the only thing which can be said is that time and heavy use had taken their toll, both of them being destroyed in spectacular accidents, first the Nieuport-Moisant 6M and shortly thereafter the Bleriot XI, in which Shakir Jerwan almost died when falling in the vicinity of the Campo de Marte aerodrome. Also, a third airplane which had been purchased by the government from the Moisant School, a Moisant BlueBird, was also destroyed three days after having arrived in the country, while it was being flown by another famous instructor of the school: Minerly Wilson. As we have seen, the true origins of aviation in Guatemala are very different from the version painted with verses richly adorned and inspired by extreme nationalism. Without a doubt, Guatemalan historians will continue to accept Nannini as the true pioneer of aviation in the country, and with reason, for very few of them know that the same Nannini -- ironically -- learned to pilot an airplane on the fields of Mineola, Long Island, having been instructed by the same Alfred "Fred" Moisant, before joining the Academy of Military aviation of Guatemala. . |

Collaborator

|

El Señor Mario E. Overall is a charter member of

Latin American Aviation Historical Society (LAAHS), where he is in charge of the computer science systems of the institution. Additionally, Mr.. Overall

performs investigation tasks, mainly with respect to the history of civilian and military aviation in the Central American region. He has

published about twenty-five articles on historical subjects in aviation magazines in Latin America and Europe. Also, he has led large

scale investigation projects such as the one of documenting the air operations of the CIA in Guatemala in 1954, the air operations

of the Guerra de las 100 horas, (War of the 100 hours), between Honduras and El Salvador, and the origins of military aviation in

Nicaragua. At the moment, he also acts as a field investigator for the Division of Archives of the Smithsonian National Air & Space

Museum , specifically for the project of the documentation of the history of aviation in Central America, and as a correspondent of the

Brazilian magazine FLAP Internacional, (FLAP International), for Honduras,

El Salvador and Guatemala. |

| Declaration of responsibility: The ideas and opinions expressed in this article reflect the exclusive opinion of the author elaborated and cradled in the academic atmosphere of freedom of expression of the University of the Air. In o case do they reflect the official position of the Government of the United States of America or its dependencies, the Department of Defense, the Air Force of the United States or the University of the Air. The content of this article have been reviewed as far as security is concerned and have been approved for public diffusion according to the directive AFI 35-101 of the Air Force. |

|