| Writers at Work |

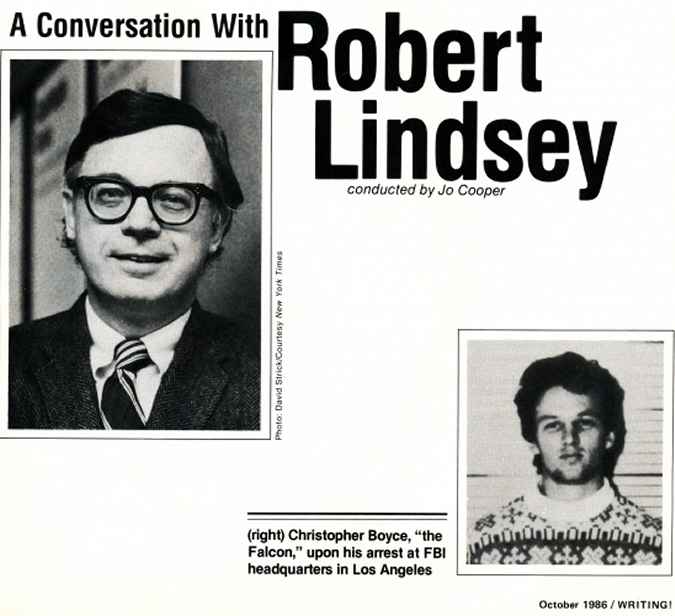

| Robert H. Lindsey is chief West Coast correspondent for the New York Times. He is the author of The Falcon and the Snowman, the true story of two young men from Lindsey's own neighborhood. Christopher Boyce and Andrew Daulton Lee, who wre convicted of espionage. The Mystery Wrriters of America awarded him an Edgar Allan Poe Award for the book. It was also made into a motion picture (Orion Pictures, 1984, starring Timothy Hutton and Sean Penn). |

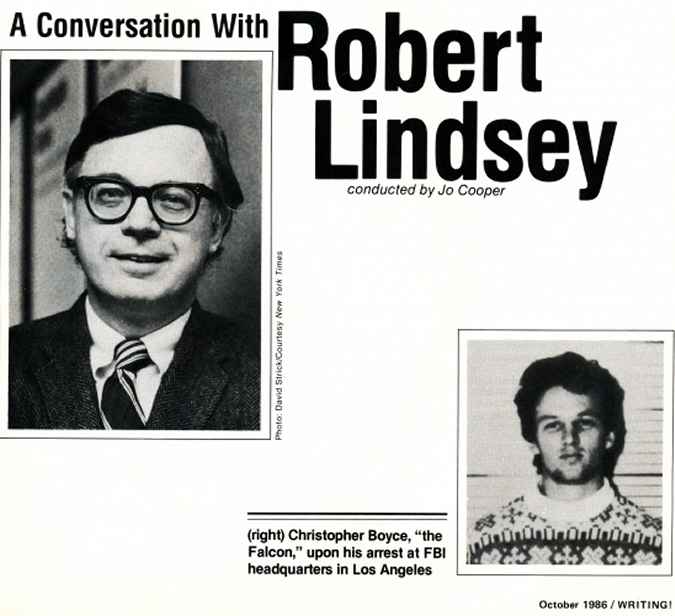

Lindseys The Flight of the Falcon is the true story of Boyce's escape from prison and the eighteen-month manhunt to recapture "The

Falcon," as Boyce was known because of his fascination with falconry. Lindsey considers both these books to be "journalistic novels." Contributing writer Jo Cooper began her conversation with Robert Lindsey by asking him about this form of writing. Jo Cooper: How do you approach the task of writing a |

journalistic novel? Robert Lindsey: What you do is apply the techniques of a novelist but use real events. You try to reconstrudt them by talking to as many people as you can, visiting the places and, if necessary, checking what the weather was like on a certain day to descrive it as accurately as possible. The first thng you should do with this kind o book is get a chronology of the dates that you can refer to. there will be |

|

|

inconsistencies, but if you have some sort of lodestone that you can refer to, you can keep it straight. It states on The Falcon and the Snowman's cover that the book is a "true story," not "based on a true story." like the movie. Is everything in it absolutely factual? It reads like fiction. Lindsey: Everything is true. I've since learned of a few inconsistencies, but when I wa writing it, it was essentially a long news story. You were assigned to cover the trial of Boyce and Lee for the Times. What, for you, made this case so fascinating? Lindsey: On a Sunday afternoon in early 1977, the New York office called and told me that two young people from Palos Verdes, California, had been arrested for espionage. I said, "Oh my God, that's where I live." I sat through the entire trial. It upset me. I wanted fo fond out what triggered thier behavior\. Here were two young men wo net as altar boys, became espionage agents for the KGB, and ended up in prison. They grew up in the same town, where

|

I lived, where my son was going to high school. I became obsessed with the idea; why did these two kids from a nice community and good families become Russian

spies? What research sources helped you to answer the question? Lindsey: I interviewed everybody I coiuld, read all the court documents, and obtained a copy of the transcript. Anything that's in the court file or entered into evidence is public record. The trahnscript is public if you want to pay to have it transcribed. The biggest break I had in writing the book was developing a relationship with the lawyers for the two defendants. They gave me access to all their redordds, whidfh wa a gold mine because people theey'd interviewed confided in them. I was also allowed to see all of the investigative redords, the FBI redfords. That was the main part of the research. The, of course, I did a lot of interviewing with Daulton lee and Christopher Boyce. Basically, I got to know Byce very gradually while I was writing the book. He was very guarded. After about six months of dealing with him, he started o open up-mostly after I had fihnisyhed the book. The he sent me letters which gave3 me a lot of insight. Our friendship, if that's what it was, developed mostly after the book was done. He would call me (left) Andrew Daulton Lee, "the Snowman" |

practically every day from the prison in Lompoc, California. In the book you include such details as the school grades and IQ's of Lee and Boyce. Did you obtain this personal information from the schools? Lindsey: No, those records had been subpoenaed by the government, and they were introduced as evidence. You also quote a psychiatric redord. Isn't that usually highly confidential? Lindsey: That came from one of the lawyers. You vividly describe Lee's torture in a Mexico City jail. How did you get that information? Lindsey: That's all from interviews with him. He wqas a cooperative source up to a point. When he realized i was writing a book, he started asking me for money for information, and since I have a policy of never paying sources, he sut me off. In the last chapter, the sory of the peregrine falcon that flew up to the prison reads like fidtion. It ties in so neatly with all the incidents involving Boyce raising and flying falcons earlier in the book. Are you sure Boyce didhn't make that up? Lindsey: Yes. The San Diego Union ran a story aobut it. They had a picture of the bird and Boyce and the prison. How did your research grow into a full-length novel? Lindsey: First I did a feature story for the New York Times Magazine. Then, Jonathan Coleman, an editor at Simon & |

|

Schuster, asked me to do the book. Naively I said yes, not realizing how difficult it would be or how much time it would take. It took me a little over a year to put it together. I

interviewed people and developed my relationship with Boyce. It was a tough project that took every weekend for a year. Then, the editors got hold of it and made changes,

and I had obtained some additional informaiton, so I rewrote it. It came out in November 1979 One criticism of The Falcon and the Snowman was that you made a spy into a hero. Lindsey: Ironically, Boyce refused to cooperate halfway through the second book, The Flight of the Falcon, because he thought I'd made the U.S. Marshal who pursued him too much of a hero. How did the second book come about? Lindsey: In January 1980, Boyce escaped from prison. The timing was so perfect that Simon & Schuster even suspected me, at first, of helping him escape. When he escaped, my publisher asked if there would be a sequel, and I said yes. I developed friendships with the U.S. Marshals, and they shared information with me. I virtually lived with them. But I had a problem on the second book in that Boyce, after first indicating he would cooperate on the sequel, shut me off. He didn't want another book written. Then I was left with the information that he'd given me up to that point. The challenge was trying to find out things form roundabout sources. I had to interview people in Idaho with whom he had lived when he was a fugitive. Writers sometimes have mixed feelings when their books become films. Were you happy with the movie The Falcon and the Snowman? |

Lindsey: Basically, I was happy with it. Steven Zaillian, the screenwriter, and John Schlesinger, the

director, both showed a desire to retain the integrity of the book. The story basically was accurate the way they told it. There were some things they included that I wasn't pleased

with, but overall I was satisfied with it. I don't think they probed deep enough into Boyce's mental anguish, or why he became a spy. Do you think you answered that question in your book? Lindsey: I'm not sure I did. In the second book, I tried to do a little bit more about it. Boyce's motives basically are in the first book, though I suspect some people will finish it and ask, "Why did he do it?" But I think the reasons are there. he was disgusted with his country, and he got a job where he was dealing with very highly sophisticated secret information. He had always been a risk-taker, an adventurer, as he called himself. Because he was disillusioned with his country, he set orf on a lark to become a spy. He thought he could tweak the noses of both the CIA and the KGB. Then he got in deeper than he ever dreamed he would. Let's leave him now and talk about you. Did you dream about becoming a writer when you were in school? Lindsey: Well, I started a newspaper in the fifth grade, and a year later my teacher, a nun at St. John's Catholic School in Inglewood, California, told me, "You have a talent--you ought to be a writer." Then in high school I had a good journalism teacher, W..A. Kamrath, who taught me a lot of what I learned about writing, or I should say reporting. I decided to become a reporter and went to San Jose State College, first as a journalism major, and then changed to a history major, |

which I think is good experience and background for a reporter. I took a job right out of college, with no real journalism experience, with the San Jose Mercury. I was lucky to have some really good editors there who were willing to take a chance on a young, green reporter, and they helped me a lot. While I was with the Mercury, I covered the aerospace and aviation news, and that's how I got transplanted to the New York Times. I got hired because I covered national stories. Did you write magazine articles:? Lindsey: I did a lot of magazine articles for the New York Times Magazine, and when I was a contributing editor for a magazine called Missiles and Rockets, which was an aerospace trade magazine. I did that for five or six years. What are you working on now? Lindsey: I am thinking about doing a book on a case in Utah involving the Mormon church. Two members of the church were killed. It involves a lot of intrigue that I still can't explain. What advice do you have for young writers who want to write journalistic novels? Lindsey: The best thing is to work on a school paper, and possibly a local newspaper, to get experience in dealing with facts and people. They will find out that some people try to hide embarrassing things. They should learn empathy. The best thinkg they can learn is the ability to put themselves in someone else's shoes and to think why the other person feels a certain way. They should look around. In almost any community, there's a story, if not currently, then in the past, that would lend itself to this kind of re-creation of an event. Stories are all around us, if we look for them. |

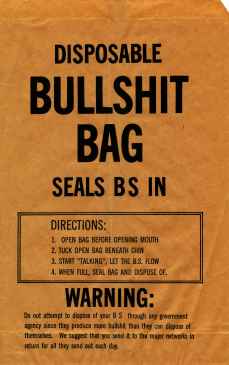

By Ralph Cooper, 12-28-07 Included among the many papers in her folder for this article were some very interesting items. Sometime in early 1986, Jo apparently contacted Chris Boyce in prison. He sent the following response: |

|

|

|

To Jo Cooper, I request that you forward the enclosed bag to the subject of your "research job" article for WRITING! magazine. |

6 inches x 10 inches |

| Sometime in 1987, Jo had sent a copy of her book, "Handfeeding Baby Birds," to Chris Boyce in the United states Penitientiary in Marion, Illinois. The book was returned to her by the officials with the explanation, "Inmates may receive hardcover books only from the publisher or a bookstore." |

|