1886-1966 |

|

|

Photo from 90 år av flyg på Ränneslätt website. |

|

|

Hugo Sundstedt with his Bleriot XI named "Nordstjernan", photo taken at Ränneslätt in July, 1912.

You can almost see the hill with the small moument in the background. The spot that the plane,

with it's small hangar is situated, is in fact quite close to the concrete pad in the beginning of

todays runway 19! This photo belongs to the museum of Eksjö' collections. Fotot finns i Eksjö museums samlingar. Photo from Svensk Flyghistorisk Förening Region Småland SFF-F website. |

September 21, 2002 Brgds, Fredric Lagerquist Norra Smålands FK and Swedish Aviation Hist Soc |

|

December 22, 2002 Here is some information about Mr. Hugo Sundstedt. Please read the text and make it more readable for people. I hope you can use it on your site and that it will extend the information regarding Mr. Sundstedt.. Hugo was born in the little Swedish town of Orebro July 12,1886 and christened Hugo Leonardsson. His mother was unmarried and already had three sons. The family lived under very poor conditions and in 1892 Hugo was sold as a working boy for the sum of 75 Swedish crowns a year to a shopkeeper.( In todays money around 8 dollars). In 1897 he became fosterchild to a merchantman, Olof Sundstedt, in Orebro. Hugo started his schooling in 1898, but was not very successful, so in 1901 he voluntered for the Swedish Navy. He ended his career in the Navy in 1904 and was employed as a bookkeeper back in Orebro until 1905. In October that year, he took a commission as a sailor on a merchant ship. He left it in Cardiff, England, February 19,1906. In December 1908, he was living in Stochholm Sweden and working as a cabdriver. He worked as a cabdriver until 1911. Next, he started his career in aviation as a handyman to the first aviator in Sweden, Carl Cederström. He worked for free, with the understanding that he would be taught to fly. His first flight was on June 1, 1912, at Ljungbyhed, with Carl Cederström's old aeroplane. It had been bought for him by some wealthy businessmen from Orebro. During one of his first longer trips, on June 21, he set a Scandinavian altitude record at 1500 meters and also made one of the first aerial transportation of newspapers in Sweden. During the month of July 1912, he was ready to take the tests for his certificate. Unfortunately, he became involved in the first fatal accident with an aeroplane in Sweden, and his certificate was delayed until the accident was investigated. Hugo Sundstedt was found not guilty in the death of a young woman who accidently was hit by the propeller of his aeroplane. After being cleared, he was given certificate number 9 in Sweden on August 2, 1912 . He was the first civilian to receive a Swedish certificate, more or less selftaught. All eight aviators before him were educated in France or England. Hugo was active in flying during 1912 to 1913. During the winter of 1914, he went to France to take possession of a new Farman aeroplane. In April, he crash-landed and was hospitalised for a couple of weeks before returning to Sweden with his new Farman. Upon arriving in Malmoe in July, 1914, he landed on a grass field and overturned .The aircraft was damaged, but when WW 1 broke out, the Swedish Navy bought it and it became flying boat number 4 in the Marine. Hugo Sundstedt was enrolled as a pilot in the Navy and was on duty until April, 1916. During autumn 1916, he left Sweden for France, but found it very difficult to find employment there. He therefore decided to travel to the USA. He arrived in New York on New Years day 1917, on the French steamer L´Espagnole. During 1919, he was involved with the Sunrise Project to cross the Atlantic. He died on July 8, 1966, in Liberty, New York This is a short history of his life and career. If anyone can offer more information about his life in the US, I really would appreciate it for I am still working on Mr Sundstedt's life. During next year, I will probably try to publish something in the aviation yearbook here in Sweden. Is it possible for you to act as a mailbox for eventual information about Hugo Sundstedt's life in America? I know he had two stepchildren from his marriage to Lorna Duveen Sundstedt. One stepdaughter Mrs Eugene M Hanofee in Liberty, N.Y. and one stepson Lionel Roy Carpenter in Hartford, Connecticut. These details come from his obituary. Best regards Lars Axelsson Editor's Note: I thank Mr. Axelsson for his very interesting contribution to the Hugo Sundstedt story. I hope someone will visit this page and will be inspired to respond with whatever help they can offer. I will be happy to relay it to Mr. Axelsson. |

|

THE SUN, SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 23, 1919. |

|

|

Photo Courtesy of Elizabeth Hanofee |

|

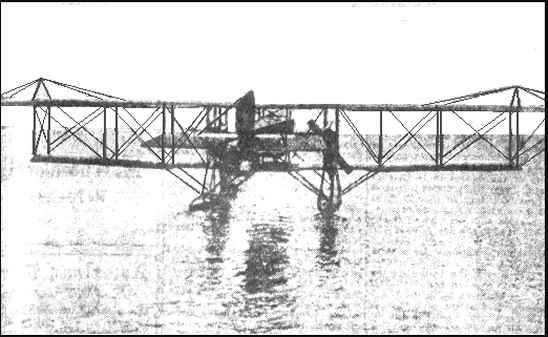

EVER since the days when a penurious young man named Edgar Allan Poe wrote for THE BALLOON HOAX in 1944, an account of the crossing of the Atlantic in three days by a flying machine invented by Mr. Monck Mason, the idea of a translantic flight has gripped the imagination of dwellers near the seacoasts of Europe and America. Never before has the accomplishmnent of this feat seemed so certain and near as now. The Governments of England and the United States are sponsoring it, and so are many private individuals and airplane companies. Everywhere aviators and aeronautical men gather it is freely predicted before 1919 is over some daring ..ger will have flown from continent to continent and reduced the distance apart from six long days ...ing, speed shaken liner to less ...on a wing splitting comet of airplane. A man who will probably make the attempt is Capt. Hugo Sundstedt, late of the Swedish navy and recently applicant for American citizenship. The machine is the Sunset, a huge seaplane of his own design. Its engines are Liberty sixes. |

|

|

|

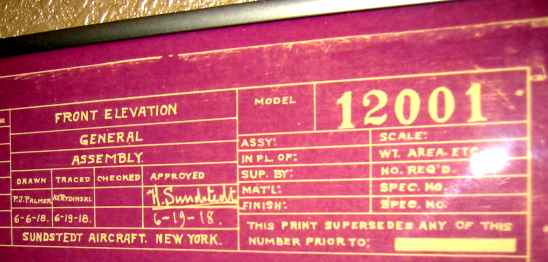

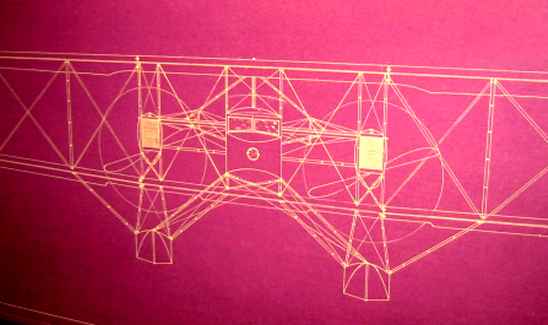

SUNDSTEDT AIRCRAFT CO. - NEW YORK Two of six photographs of the blueprint. Editor's Note: Matt tells me that he hopes to find someone who wants this unique bit of history for his own collection. If you are interested, please let me know and I will pass along your email to him. |

|

There are three important factors, the size of the machine and the route, the ..undoubtedly the most

interesting .,..it was who built the machine and the route. In appearance Sundstedt is not a typical aviator. He is not a lean, lithe

youngster, ...moving, with a nose like the beak of a falcon and piercing eyes to match. Then, although any reader of fiction will agree

that this is a perfect vision of the outward appearance of an aviiator, few of the real aviators have been hanging up records running

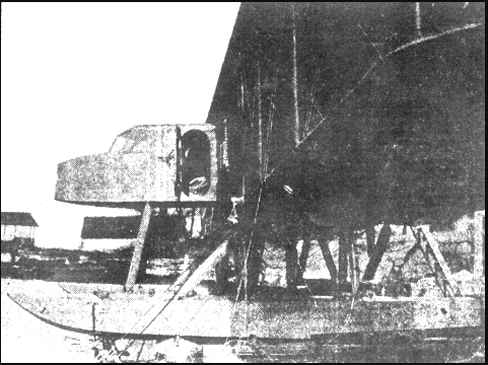

down Germans look at being "typical aviators." Actually, Capt. Sundstedt is a heavy man of about 33, of medium height, regular features, and almost black curly hair, worn longer than is usual, and reenforced by short side whiskers. His movements are invariably deliberate; so is his speech, and beyond an occasional smile his face is immobile. His temperament is of the coolest, as is proved by various incidents which have occurred recently at Bayonne, where his is extremely busy getting his seaplane ready for a winter journey in high latitudes across the Atlantic. On the day she was launched the plane, moving diagonally out from shore instead of straight ahead, on account of unequal engine speeds, crashed into a small landing dock, shivering the stout handrail and shattering the taut strung nerves of the builders and friends of the aviator, who were watchng from shore. A wing of the plane herself was nicked, but not so Capt. Sundstedt's calm. Then came a day when, after the damage done had been repaired, the seaplane cast off for her trial flight on the broad and little traversed waters of Newark Bay. As she drifted northward the air starter was tried, but failed to spin the huge propellers. For a good part of the afternoon, as she slowly drifted up the bay, the mechanics tinkered with the air tank unavailingly. The plane was towed back and the chilled crew hastened to the warm rooms of the Puvonia Yacht Club, which volunteered accommodations for the Captain and the plane. Then came gales from the north and prevented testing for several days. Throughout all these mishaps the Captain remained calm. "No, I have had no bad fortune," he declared when sympathy was offered. "These things always happen when a new plane is tried out. They are flea bites. I am in no hurry to get started, except that I must start before anyone else does. Before I go the seaplane will be tried on the water, and in the air empty, with half her load of gasolene and oil, and then with the full burden. But when we do go we will go fast." Aside from his naturally phlegmatic disposition it is probable that Capt. Sundstedt's seeming indifference is due to his long experience with both air and water craft. A seaplane is a hybrid, and it has all the perversities as well as the virtues of both aerial and aqueous parents. Capt. Sundstedt's sea education began when at 13 he became a cadet in the Swedish navy. For ten years he devoted himself to the sea, and then at 23, in 1909, he became interested in the new American invention, the airplane. On frequent leaves from the Swedish navy he visited France and other countries, examining aircraft, studying them, and finally combining his knowledge of sea and air for the benefit of the Swedish navy. He attracted the attention of Henri Farman during one of his trips to France, and the famous French aviatior predicted great things of him, saying that he was a first class aviation expert. In 1914 Capt. Sundstedt proved Farman's opinion good. In July, 1914, the month before the war, the Captain, then in Paris, purchased a Farman biplane, a good machine as machines went on those days of frequent mishaps and invariable breakdowns, when any flight at all was considered worth space in the papers and many accounts of flights were also obituary notices. "How are you going to get it back to Sweden?" a friend asked him, thinking of the trouble and expense of transporting the bulky machine over half of Europe. "Fly it," he replied, and that was what he did. Indicentally in making the flight, about 1,200 miles, Capt. Sundstedt made a non-stop record which, it is believed, remains unbeaten today. His time for the flight between Buc, France, and Stockholm was thirteen hours and twenty minutes. His knowledge of aviation proved of much value to him in connection with his work in the Swedish navy, and he was rapidly advanced until he reached the rank of Captain and commanded the flying station at Carskrana. While in the navy he made at least eight flights of more than 1,000 miles. During 1912, 1913 and early 1914 the German navy, for reasons best known to the late Imperial German Government, was extremely busy in North Atlantic waters. During naval manoeuvres great observation balloons and airplanes were sent aloft, and within a short time the German Government became possessed of a great mass of data which showed precisely the strength, direction and period of various air currents that had not been known before. Capt. Sundstedt was able as a Captain in the Swedish navy to secure charts and much more of this information. It furnished what he believed was a solution of the problem of flying across the Atlantic. For an air current flowing at a rate of from fifty to seventy five miles an hour was shown some distance north of the northernmost steamship lane and more than two miles above the surface of the earth. This current, according to Capt. Sundstedt, travelling always from west to east, is constant and reliable. For several years he studied it and the fogs around the coast and banks of Newfoundland, and various other meteorological phenomena of the North Atlantic. After satisfying himself that he had absolutely accurate information about a condition which would aid materially in the transatlantic flight, Capt. Sundstedt and a companion, Lieut. Kiel Nyegaard, a French military aviator of Norwegian birth, came to the United States in December, 1916, to make arrangements here for the building of an airplane in which to attempt the flight. Then the United States entered the war and the attempt had to be indefinitely postponed. Lieut. Nyegaard returned to France, but Capt. Sundstedt remained and took out his first citizenship papers. Although he could not fly he planned, and planned so ingeniously that Christopher Hannevig, a Norwegian banker, became convinced that Sundstedt really could fly across the ocean. He furnished the financial backing necessary, for the Captain himself was not wealthy, and last July the Captain began the designing of the great seaplane which is now ready. Add the fact that he has in the cabin of his transatlantic flier an image of an elephant with upcurled trunk and always carries with him when flying a similar charm, and his portrait is complete. The seaplane he designed differs from other big hydroairplanes chiefly in its lighter weight, for Capt. Sundstedt during his years of study in preparation for the trip spent much of his tijm on the elimination of heavy parts and the substitution of equally strong yet lighter ones. Balsa wood, 30 per cent lighter than cork, enters largely into the construction of parts where great strength is not required. The two pontoons, for example, although thirty-two feet long and extremely sturdy, weigh only 400 pounds each and are capable together of bearing a weight of fourteen tons. The great upper wing of the seaplane stretches a chord of 100 feet, the lower 71 1/2 feet. Her length, from the tip of the cabin projecting in front between the two wings to the end of her rudder, is 50 feet. Her height is 17 feet. The total weight of the craft itself empty is 7,000 pounds, although seaplanes of this size usually weigh 4,000 or 5,000 pounds more. The cabin is fashioned out of the forward projection of the fuselage or longitudinal framework of the craft and contains seats for four persons, two pilots, who will be Capt. Sundstedt and Lieut. Paul Micellli, a pilot of the Uintied States Army, and behind them two mechanics. Either pilot may fly the machine, for Capt. Sundstedt will need relief during the flight, when he sets, with the usual navigation instruments or by the stars, the course he has already determined on. A dashboard in front of the pilot holds all the insturments needed, as well as a navy compass hung in gimbals. Two Liberty engines, built by the Hall-Scott Company, propel the craft. The engines are either side of the fuselage, between the wings, and the propellers are bolted directly upon them. Each engine is of 220 horsepower. If anything goes wrong with one during the flight a mechanic can step from the cabin on to the strong lower plane and make repairs without difficulty or danger. The engines make 1,400 revolutions a minute. In the fuselage behind the cabin is stored the supply of oil and gasolene. There is room and carrying capacity for 100 gallons of oil and 750 gallons of gasolene, enough, the aviator is sure, to carry him safely with the aid of the fifty mile wind current over the long leg of his flight. The speed of the engines alone, the captain believes, will send the seaplane roaring through the air at eighty miles an hour, and the fuel he carries is enough for twenty to twenty-two hours, according to his calculations. The Liberty engines have already shown their power and endurance in eighteen hour tests in San Francisco. The propellers, nine feet long, have two blades, and are set behind the engines. The fuel, oil and crew carried will total about three tons, so that when fully loaded machine and cargo will weigh six and a half tons, a weight which will of course decrease as the gasolene is exhausted. When the day of the great attempt comes--Capt. Sundstedt said it would be early in March if the machine should test up to expectation--the Sunrise, true to its name, will rise into the air some morning as the sun's first rays strike the water of Newark Bay and head northeastward, following the coast of the United States up to St. John's, N. F. This trip, the Captain estimates, will take about ten hours, so that the landing at the other end will be made in daylight. After a stop over night to replenish fuel and food and look over the seaplane, Capt. Sundstedt will continue his trip at 4 the next afternoon. St. John's is 1,700 miles almost due west of Queenstown, Ireland, but the route taken by Capt. Sundstedt will be further to the north. He will fly in this direction, rising to a height of more than two miles to get into the cold air current which he knows is waiting for him. Without this current--although Capt. Sundstedt himself is too much of an optimist to admit it--it is probably that his seaplane would use up its fuel supply before the Irish coast was sighted. With it he feels sure that he will be able to fly all the way to London without stop in about sixteen hours. He must stop at London, for it is there that he will claim the prize offered hby the Daily Mail of $50,000 for the first transatlantic flier. Whether or not the flight succeeds Capt. Sundstedt wants it known that it is strictly an American attempt; is he not almost an American citizen? And was not his American built seaplane christened with American champagne by an American girl, Miss Erna Steinway, who is soon to become his American wife? |

|

|

Photo Courtesy of Elizabeth Hanofee |

|

|

|

Library of Congress Collection, 5-13-11 |

Library of Congress Collection, 5-13-11 |

|

from Flying May 1919 p 374 The machine was piloted by Commander Seversky, a Russian naval aviator, who was accompanied by Lieut. Baker, a United States army aviator. Commander Seversky banked the machine while landing. It went into a sideslip, and the pilot lacked altitude to recover. Neither Captain Sundstedt nor Lieut. Paul Micelli, his aid, were in the machine at the time. Captain Sundstedt said the accident probably would eliminate his machine from the trans-Atlantic contest. "It will require at least a month to construct new pontoons," he said, "and by that time some of the present entries undoubtedly will have made the flight." The damaged machine was the first aeroplane to be entered for Lord Northcliffe's $50,000 trans-Atlantic contest. Lieut. Procofieff-Seversky who had consent4ed to take the plane across the Atlantic, was up about 300 feet when the accident occurred. The plane was damaged, and must have new pontoons. That work will take about two weeks, and then, the Lieut. Commander said he will start for Europe. He is 25 years old, and for four years has been engaged in naval aviation. Recently he made flights in Buffalo for the United States Government. |

|

Hugo Sundstedt, 55 West 55th St., New York, aeronautic engineer. French Aero Club Ctf. 9, of 1909, Stockholm. courtesy of Steve Remington - CollectAir |

|

A nice biography of Hugo may be found on the Wichita State University Special Collections and University Archives website by clicking on: Hugo Sundstedt |

|

|

"To James Duffus

Mr. Duffus was a broadway actor/singer in the early 1900's & "Afgar" refers to a

production in which they worked.in memory of "Afgar" Very Sincerely, Erna Steinway. March 22, 1921 |

|

From The Early Birds of Aviation Roster of Members January 1, 1993 If you have any information on this Early Bird, please contact me. E-mail to Ralph Cooper Back

|