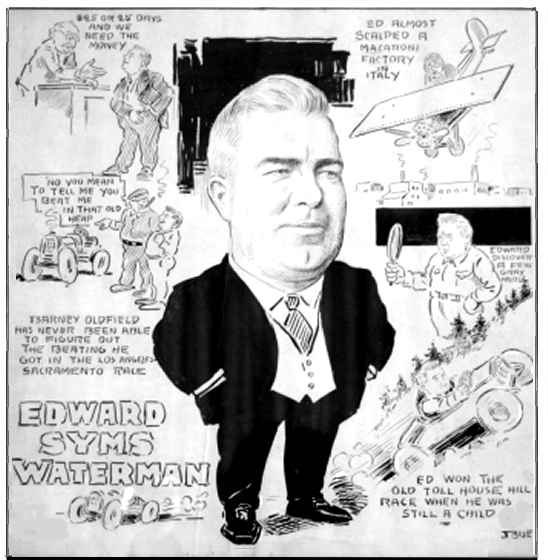

1893- AKA Eddie Waterman |

|

Collection of Gena Blair, 2-24-08 |

|

via email from Eric Coyne, 12-23-03 |

|

Collection of Gena Blair, 2-24-08 |

|

Panama-Pacific Road Race By Eric S. Coyne (c) By the time Californians began preparing to celebrate the nation's natal day in 1913, auto racing was a well-established sport with legions of avid fans. Enterprising automobile dealers had taken notice of that often paraphrased purchasing phenomena: Race it on Sunday and they'll buy it on Monday. The power of this formula wasn't lost on George and Edward B., owners of Waterman Bros., Fresno's largest automotive dealership. They handled sales for the Winton, White, Buick and Reo lines. Waterman Bros. sent in an entry for 20-year-old Eddie Syms Waterman, George's son, to drive a 1910 40-hp Model 17 Buick. Waterman Bros. also sponsored a second Panama-Pacific entry? Reo No. 26 ? to be driven by Fresno driver Earl Jackson, a speed pilot of some renown. Endurance races such as the Los Angeles to Phoenix Road Races - held from 1908-1914 across the Southwest's trackless stretches of desert wasteland - passed into the fabled lore of early motoring as drivers' trials and tribulations were recounted by eyewitnesses and magnified upon in many publications of the day. Such would be the fate of the men who would compete in the Panama-Pacific on July 4,1913 - noted drivers such as Barney Oldfield; Louis and Fred Nikrent; Frank Verbeck; W. H. "Coal Oil Billy" Carlson Jr.; Glover E. Ruckstell; Gaston Morris; Sam McKee and Charles Soules. Organizers obtained a sanction from the Western Automobile Association and lost no time promoting the event up and down the Golden State. Auto editor Bert C. Smith of the Los Angeles Daily Times and the famous Australian "speed king" Rupert Jeffkins motored the length of the Central Valley. They made a show of scouting out potential routes in a huge chain-drive FIAT racer with the legend "L.A. - S. F. Grand Prize Road Race; $50,000 - 50 entries" painted prominently on the hood. "Terrible" Teddy Tetzlaff and Panama-Pacific race chairman Leon Shettler also made many a scouting trip between Los Angeles and San Francisco - the race's originally scheduled destination. The stated reason for these early trips was to determine which way to route such a race - along the Coast or through the Central Valley. However, the resultant publicity also helped accomplish two other important objectives: The promise of a large winners' purse persuaded many top drivers to enter cars and also helped solicit generous "sponsorships" from merchant associations and town councils in key towns. Subscriptions were pledged in exchange for Shettler's promise that these same towns would become checking stations for the Panama-Pacific racers. Within weeks it became apparent that racing through dozens of Valley towns would draw far bigger crowds and be vastly more lucrative for promoters than skirting along the sparsely populated Coast. Soon Bakersfield's city fathers stepped forward and offered the Panama-Pacific race committee\ $5,000 in sponsorship money with the understanding that the Pan-Pacific racers would arrive in their town by early morning and make a fast lap around the new racetrack Bakersfield had just spent $100,000 constructing at the local fairgrounds. Shettler promptly agreed to start the race at midnight, with the first car set to drive away from the starting line in Los Angeles at midnight on July 4 and the rest of the cars to start at two-minute intervals thereafter. By June the route seemed sure, and snaked through the Valley from 11th Street and Figueroa in the heart of Los Angeles over Tejon Pass and the Ridge Route, then north through Valley towns such as Bakersfield, Fresno, Merced and Modesto. After passing through Stockton, racers were to continue on through Tracy, Livermore, swing through Milpitas and Mountain View, and then on north to San Mateo before making a final sprint to the finish around the racetrack at Tanforan. But just days before the Fourth of July, organizers suffered a severe setback when officials in Santa Clara and San Mateo counties refused to waive the speed limit for racers if they passed over public roads in those areas. This was devastating news for Shettler. No one wanted to watch drivers the likes of Barney Oldfield rein in their big Nationals, Stearns, Stutzes, Alcos and Appersons and putter along to a big finale at 10 mph! Shettler hastily persuaded Sacramento officials to host the terminus of the race, and to ensure that the Panama-Pacific would be an all-out battle with no speed restrictions. The word went out; records would certainly be broken! Although 51 car owners each paid a $250 entry fee and were listed in the program as official entrants, only 49 cars would actually start the race. Ralph Chandler and Dominick Basso crashed while practicing the night before the race in the mighty Alco ? the very same car that won the Vanderbilt Cup race in 1910 and 1911 - struck a horse-drawn camp wagon and shattered a 10-inch telegraph pole. Basso was to drive the big Alco Vanderbilt Cup car bearing entry No. 32 in the Panama-Pacific; Chandler was scheduled to race Alco entry No. 30. Press reports said while traveling at approximately 60-65mph "like a comet in the night," the Alco rounded a corner and struck a wagon loaded with seven people. The L.A. Daily Times reported the two men were thrown 50 feet, the horse was killed, and the Alco did two complete somersaults. R. L. Draper's Metz No. 46 failed to report to the starting line, further narrowing the field before midnight. As required by race officials, contestants arrived at the staging area at Fiesta Park two hours before the start and lined up four cars abreast. City officials had predicted more than 150,000 spectators would turn out to watch the start and line the streets along the r acers' path out of town. Los Angeles Mayor-elect Henry H. Rose fired the pistol shot that launched the first racer into motion at the stroke of midnight on July 4. Starter William R. Reuss then began to send away the remaining road racers at two-minute intervals according to their entry numbers. It would be a full hour and 41 minutes before all 49 racers could get underway. The starting field of 29 different makes included Jack Fleming's magnificent Pope-Hartford; two Buicks; four Mercers; E. T. McConner's Lancia; a seven cylinder Macomber rotary; Olin Davis' Locomobile and Tulare racer George M. William's Pullman. Charles Soules was first away in Cadillac No. 1, the deep-throated roar of his big four-cylinder echoing raucously off the buildings lining 11th Street to Hoover Street, then north to Los Feliz Road before sweeping eastward. Al Faulkner started second and drove one of five big Simplexes entered that day. Not far behind came Omar Toft in Simplex No. 5, entered by wealthy Los Angeles socialite Leotia K. Northam. Barney Oldfield must have grown impatient, forced as he was to wait for Reuss to wave the starter's flag that would propel him forward in a mammoth 120-hp FIAT Model S74, entered with Oldfield's lucky No. 7. T.J. Beaudet motored off in Don Lee's Cadillac No. 8 at 15 minutes after midnight. The next away was eventual winner Frank Verbeck, a Pasadena chauffeur driving a 45-hp Fiat entered by E.E. Hewlett, principal owner of Pacific Motor Car Company, the West Coast FIAT dealer. Francis Gage, son of former California Governor Henry T. Gage, a millionaire mining magnate from Santa Clarita, waited patiently behind the wheel of car No. 39, the Welch, for his turn to start. Gage's bride, the former Miss Amy Marie Norton, sat beside her husband in the mechanician's seat until just before it was time to dash forth. Mrs. Gage kissed her husband goodbye just before he was sent away, promised to see him the next day in Sacramento, and jumped into another car, which was to follow the racers. Motorcycle patrolmen escorted each Panama-Pacific racer from the starting line and on their way out of town via Los Feliz Road to San Fernando Road. At this point drivers were allowed to accelerate along the smooth macadam on through the first checking station at Tropico to Glendale and Burbank, climbing their way up through the San Fernando Valley and over the pass into the Santa Clarita Valley. The route passed through Saugus and onto the tortuous, twisted roads of San Francisquito Canyon The 23-mile stretch of road and 1,600-foot climb up through the canyon to Elizabeth Lake was widely considered to be the most dangerous part of the course. Elizabeth Lake, nearly 60 miles distant from Los Angeles, was the second checking station. From there the racers trundled up the Tejon Grade to Bakersfield, the third checking station. The course then led north, with checking stations at Terra Bella; Porterville; Lindsay; Fresno; Merced; Modesto and Stockton before concluding with a final sprint lap around the fairground track located in Sacramento's Agricultural Park. Mechanical calamities, bad roads, a foggy run through the night and fatigue would eventually narrow the field. Drivers had to plow their way through more than 40 creeks during the trip from Los Angeles to Bakersfield. Only 19 cars would officially finish the long trip to Sacramento. William W. Bramlette's Apperson No. 4 ran into a ditch at Tropico seven miles from the start and was the first car out of the race. Neither driver nor mechanician was injured, but Bramlette lost control of his Apperson while turning off Los Feliz Road onto San Fernando Road at too great a speed. Then L. L. Monroe of Burbank, driving car No. 16, was forced to quit a half-mile north of Burbank. The lights on Monroe's Touraine Six went out on a curve and the car plunged through a barbed wire fence. The Touraine's radiator, fan belt and all four tires became damaged as the car plowed 400 feet through a barley field, pushing a goodly portion of the prickly fence along with it. The car was forced to return to Burbank, but a new start was made at 3:30. The Safety Gas Saver Company's Winton, car No. 22 driven by Dave Kapuczin, ran into a ditch between San Fernando and Newhall. The Macomber, entry No. 11 driven by P.E. Leach, blew one of the seven pistons in its unique rotary engine before it got out of the city limits, but a new start was made and it reportedly passed Saugus 3 hours and 55 minutes after it started. The ill-fated Macomber began developing clutch troubles, but would eventually limp into Bakersfield - only to be disqualified for arriving there 10 minutes too late. Fiat driver Frank Verbeck won, finishing with an overall time of 11 hours, one minute and 16 seconds, but not without meeting adversity head-on, as he related in a first person account printed in the Los Angeles Evening Herald on July 5, 1913: "I got lost three times on the way to Bakersfield and had to back up several miles," Verbeck said. "About thirty miles from Bakersfield I missed the road. I was near adobe station when Beaudet in his Cadillac came up. I saw his headlights and cut up through a field. Beaudet passed me. He made a sharp turn through a gate. I went after him." Struggling to see in the dim lamplight, Verbeck smashed into a fence post. "I hit the post and cut it off clean. I thought I was through right there, but the old car kept moving. The smash bent the front axle badly and almost jerked the wheel from my hand. It took all the strength I had to keep the car in the road after that." Verbeck passed Beaudet and caught up with Soules at Bakersfield, where Harry Ham, who drove for awhile so Verbeck could rest, replaced Verbeck's mechanician Charlie Willeford. "About five miles out of Bakersfield we hit a fierce chuckhole. When we came down we did not have any tire rack. We stopped and picked up one tire and I tried to hold it, but could not, so I threw it off the road and trusted to luck." Hamm was closely following Soules when Verbeck's Fiat broke an oil line near Goshen Junction and lost fifteen minutes. Repairs were quickly made. At Merced Verbeck took the wheel again and drove all the way to the finish. Later Verbeck told reporters winning the race was satisfying but exhausting work. "It'll take money to send me over that course again," he said. "The pace was killing." Eddie Waterman's Buick No. 45 wasn't scheduled to leave the starting line until an hour and 27 minutes after Soules departed in Cadillac No. 1. Waterman would finish second, but his prize money wouldn't come easy. Many critics discounted Waterman's chances long before he reached the first checking point. Waterman's late start forced him to travel along a race route torn up by the dozens of competitors who proceeded him. And those who would find fault noted his homemade Buick racer had been cobbled together from the remains of a $50 rental car that had seen rough treatment in Coalinga's oilfields. He would get lost three times and be forced to backtrack after steering down a branch road near Lake Elizabeth, but Waterman was lauded as a hero after he made a triumphant arrival in Bakersfield. "We sure didn't come through on the strength of encouragement," he would tell a L.A. Evening Herald reporter. "We passed twenty-seven cars on the way and were eleven minutes ahead of the field at Bakersfield." The plucky driver's Buick began running on just three cylinders at Famoso, but Waterman pressed on that way for 110 miles and arrived in his home town of Fresno in second place overall ? ahead of speed marvel Barney Oldfield's gargantuan FIAT. A quick 20-minute valve job and magneto cleaning in the pits set the Buick right again. Oldfield hit a milk wagon near Porterville, but later claimed no damage was done to either the wagon or the machine. A larger than life hero whose flair for self-promotion was second to no one of his era - save possibly circus showman P.T. Barnum - Oldfield fought a brave battle in his quest for victory that day. Ever true to his reputation, the charismatic driver always had a ready quote for the eager press boys: "Near Fresno, while running 85 miles an hour, a big St. Bernard dog stopped in the middle of the road," Oldfield deadpanned. "I felt a little tremble in the car - that was all. [Oldfield's mechanician George] Hill looked back, but said he couldn't see any of the pieces." Soules Cadillac finished fourth, and "Coal Oil" Billy Carlson, who had never been over the route before, came in fifth driving the No. 30 Alco originally entered by Ralph Chandler, who had been injured while practicing for the race the night before. Flemings's Pope-Hartford finished sixth, followed by the National driven by Merced merchants Charles Patmon and Barcroft. Omar Toft brought his Simplex in eighth; Hanashue and Herrick were ninth in another National, and Beaudet's Cadillac, the last car to finish in the money, arrived in tenth place. Mechanical misfortunes continued to plague the racers. Louis Nikrent's little 20-hp Model 25 Buick, car No. 18, blew out the two front cylinders when it was only 18 miles from Sacramento. Nikrent still managed to finish in 16th place. The tank on the back of the radiator in Kissel Kar No. 20 broke loose near Bakersfield, leaving the driver and his mechanician to battle this problem all the way to Sacramento. The Sacramento Union reports the arrival of Holtville Moon auto dealer P. D. Gochenouer's car No. 23 was signaled with some hilarity. The last Panama-Pacific racer to officially finish, the 60-hp Moon arrived at the fairgrounds in Agricultural Park 27 minutes behind the Kissel. Someone asked Gochenouer whether he had any trouble. "No," he replied. The race fan persisted, and questioned Gochenouer about his trip. "Oh, it was a fine joy ride," the Moon driver said. "Well, what was the matter?" said the exasperated bystander. "Matter?" murmured the driver, "why the blame machine just wouldn't go fast enough." In 1917 the California legislature passed a law barring speed contests from being held on public roads. This law ensured the end of town-to-town races. No sanctioning organization would ever repeat the likes of the Panama-Pacific -- at least until May 24, 2000. Editor's note: Eric S. Coyne is writing books on the Panama-Pacific Road Race and the Visalia Road Races held from 1912-1917. He is looking for photographs, scrapbooks and memorabilia that relate to these events, and can be contacted at 559-967-8296 |

|

Editor's Note: If you have any more information about this early aviator, please contact me. E-mail to Ralph Cooper Back

|